How Paris Gets Fed

The central question of economics is "how Paris gets fed," that is how billions of people cooperate on a global scale to procure food, clothing, and shelter, not to mention a whole lot more.

Ever since Frederic Bastiat posed this thought experiment, food–and the marvel of the grocery store more generally–has been a staple of "mere economics" pedagogy the world's classrooms over. As it should be.

Even so, the grocery store still gets short shrift as a pedagogical device. Economists should use even more grocery store examples than they do.

If someone received the odd assignment to teach an entire econ course, using only grocery store examples, it wouldn't only be a joy.

It'd be easy.

Easy doesn't mean we have all the answers, though. In fact, a grocery store is the economic naturalist's natural habitat.

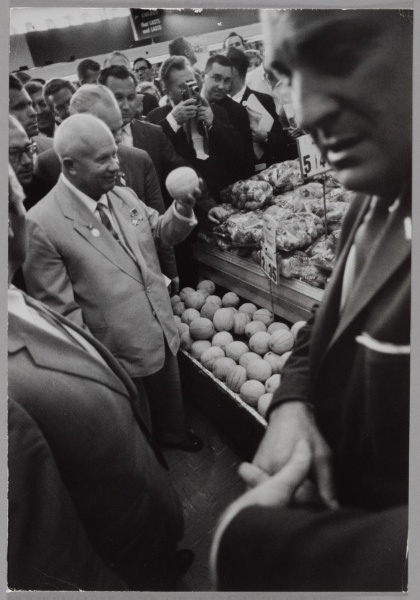

- Start with the classic question. How does the price system accomplish the world's work? The typical Walmart Supercenter, for instance, carries over 140,000 items. There are a few million more you can order from Walmart.com. But you shouldn't take this for granted. Many societies are manifestly not well-fed. Nikita Krushchev's mind was reportedly blown when he visited a run-of-the-mill American grocery store.

Then, allegedly, something similar happened to Boris Yeltsin, who even suspected his American tour-guides had taken him to some sort of Potemkin grocery store.

Is it any wonder? Their grocery stores looked something like this (but worse, because 1989 was better than 1959, the year Krushchev visited):

- Speaking of the USSR, I have an easy hack for making yourself feel better about how your day is going, how your career is progressing, or how your kids are behaving: Compare yourself to a Medieval peasant. You'll immediately feel better about whatever "it" is. For reasons far beyond the ability of this short post to explain, we are fabulously rich; they were dirt poor. We can choose from 142,000 items at Walmart for a few hours' labor; they eked out a backbreaking living in order to die an early and painful death. The product variety found in the lowliest grocery store dwarfs what your peasant ancestors' consumed over the course of their entire lifetimes.

- Grocery stores are full of brands. Brands make the world go round. They communicate scarce and valuable information to consumers about product characteristics and even provide "negative information" about rivals. They also serve as a credible commitment to provide quality. Imagine a Paul Samuelson-esque world in which competition is allowed, sure, but brands aren't! Run this mind-bending thought experiment to see just how integral brands are to the market's competitive process. What, exactly, does it even mean? Perhaps you're still allowed to cut your prices. But can you tell anyone about it?

- How do Yoram Barzel's famous measurement costs change the pricing, packaging, preservation, and purchasing of food–especially produce? Barzel explains, for example, that the same tomatoes cost less when they're packaged together than when they're sold separately. Can you explain why? No. It's not economies of scale.

- What about Steven Landsburg's mysterious, ever-growing grocery carts? Non-economic explanations don't cut it. People aren't getting "tricked," Ralph Nader-style. As Landsburg explains, that might (it doesn't) explain why shopping carts got big, but not why they get bigger.

- Remember how everyone freaked out when Amazon announced it was buying Whole Foods? The hysteria was hilarious in hindsight: The merger generated lower grocery prices, overall. Great opportunity to discuss vertical integration, mergers, economies of scale, capabilities, and antitrust.

- Speaking of competition, how about that A&P? By one measure– number of stores–it's the most successful franchise company in U.S. history. In 1930, it boasted a jaw-dropping 15,000 stores in a population less than half our current size. But past performance is no guarantee of future success, least of all in dynamic, market economies.

- The minimum wage. It's a big reason you punch those germy kiosk interfaces when you check out. But, you say, the real minimum has been steadily falling for years. Thank you, inflation! True enough, but business owners have to anticipate future hikes. There's little reason to suspect the minimum wage political football will cease getting tossed after almost a century of scoring touchdowns for politicians.

- Does your grocery store exploit you by putting the milk in the back? Is it a clever ruse to get you and your rumbling tummy to walk past all the other, irresistibly tasty treats on your way to pick up an essential? Lots of people think so. But if your argument implies "exploitation" is running wild in a market free of governmentally-erected entry barriers, your argument isn't very good. Milk is in the back because that's the best way to keep milk cold. And keeping milk cold keeps costs down, which means consumers pay lower prices for everything in the store, not only milk.

- Sticking with the exploitation theme, why are food prices so often higher in poor neighborhoods? Are capitalists sticking it to the disenfranchised? Actually, no. Think about this way: Capitalists are either gouging the poor or they're voracious, profit-hungry animals who only see green. Pick one. You can't have both. If capitalists are "overcharging" the poor for food, that means there's a large (and obvious) profit opportunity for some other entrepreneur who likes the color green more than he dislikes the down-and-out. As Thomas Sowell famously explains, prices are higher in poor neighborhoods because all sorts of costs of doing business are also higher. You need more locks on your doors. Your property insurance premiums are higher. There are probably a million other little things raising costs too. It might use more gas for a semi-truck to carefully and slowly navigate the inner city as compared with a suburb where turns aren't as tight and parking is plentiful.

- Did someone say high prices? Are high food prices due to grocery store concentration, or even grocery store collusion? No and no. High and rising prices in recent memory are but one symptom of all the money-printing that's been going on. This is also a great place to discuss the so-called Alchian Boomerang. Consider the market for beef. Consumers get more money because the Fed printed it. They spend some of it on beef, which causes butchers to draw down inventories. They put in more orders for meat, on up the supply chain (really, the supply web). There's a natural limit, though: It takes time to create new cows. With all these butchers competing for the same number of cows, the farmers raise their cow prices. That increased price then gets transmitted back down the supply chain with the butcher reporting to his customers something like: "Sorry. I have no choice. I'm raising my prices because my costs have gone up." See how this misdiagnoses the problem? What looks like costs driving prices actually started when consumers had more money burning a hole in their pockets.

- Why do we grow sugar in North Dakota and why is all our food filled with high-fructose corn syrup (i.e. poison) and why are these really the same question? Sugar protectionism is the answer. Tariffs and quotas on sugar do (at least) two things. First, they make it profitable for extremely inefficient American farmers to grow sugar. Second, they raise the price of sugar as an input, causing food producers to substitute HFCS.

- Related, Paris doesn't just get fed. It gets fat too. My sense is that economists don't understand the drivers of obesity well, but they're working on it. Gordon Tullock and Richard McKenzie have an interesting chapter on it in The New World of Economics. High fructose corn syrup-inducing tariffs aren't helping. But this is a good opportunity to discuss method: Most phenomena aren't mono-causal. Another counterintuitive contributor is probably, and ironically, the sophisticated treatments for obesity we now possess. It's far less risky to get fat in 2025, as compared to 1925.

- What economist hasn't taught price discrimination using grocery store examples? You have the classic example of third degree price discrimination in coupons. And you can discuss second degree price discrimination via bulk discounts.

- If the the food stamp program isn't a pedagogical cornucopia, nothing is. I'll take this opportunity to quote from Mere Economics:

- "Food stamps raise demand for approved foods: browsing Amazon for foods people can buy with funds from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), we find Corn Flakes, Corn Chex, Corn Nuts, Corn Pops, corn chips, corn tortillas, cornmeal, cornbread mix, corn salsa, canned corn, creamed corn, and popcorn, plus all sorts of other corn derivatives like corn-syrup-sweetened soft drinks and candy corn (first ingredient: sugar; second ingredient: corn syrup). The loud part of the food stamp program is that it helps poor people buy food. The quiet part is that it passes some of the taxpayers' money to corn farmers through the pockets of the poor."

- I'd like to know about stores' contracts with suppliers. Are they relational or highly specified "Neoclassical" contracts? Surely, the answer must differ based on the type of product. What sorts of contractual provisions do suppliers and grocery stores use to safeguard the transfer of highly perishable items? Alaska Packers v. Domenico– a staple of Law and Econ courses– arose from a dispute between shipowners and fishermen. The owners caved to labor's wage demands to avoid spoilage of the catch. But when everyone got back to shore, the owners paid what the original contract stipulated. The fishermen sued (and lost). So, you can see one reason, among others, why perishable items are tricky.

- Speaking of fish, there's a deeply fascinating (and growing) literature on global fish markets. All sorts of questions jump out. Where and why is there price dispersion in these markets? How do sellers adjust prices for highly-perishable goods, like fish? Most interesting to me, "the organization of fish markets varies from location to location with little obvious reason." What this means is that, in some fish markets, there is "pairwise trading" without "posted prices," whereas in others, there are auctions. We don't currently understand this organizational variation. The answer probably has something to do with transaction costs because, frankly, most correct answers do.

And I'm sure I'm only scratching the surface. So, grab a cart. Let's go shopping!