Five Ways Minimum Wage Studies Fail - Margins of Adjustment

Here at the Mere Economics blog, Art Carden and myself plan to explore how "people expand their options by cooperating" - to borrow from our forthcoming book.

To kick things off, I want to revisit something that impedes cooperation: the minimum wage. The following is a selection from a piece I originally published at The Independent Institute.

Teaching in the smartphone age means students are never more than a few seconds away from the dreaded “fact check.” In Econ 101, I frequently receive questions about studies showing that the minimum wage does not generate unemployment. Such studies have become something of a cottage industry since Card and Krueger (1994), a landmark study comparing Pennsylvania and New Jersey, purporting to demonstrate no harmful effects on employment from the minimum wage.

However, it would be short-sighted to conclude from such studies that the minimum wage generates no job loss. In some cases, even well-designed empirical studies can obscure the presence of disemploying effects.

I’m not against empirical studies—I think there should be more of them. But empirical work is complex, and it ought always to be guided by theory. I hope that economists think more carefully about how empirical work can fail to show job loss where it is, in fact, present. High-octane labor economists have been doing just that in recent years. David Neumark, William Wascher, and Jeffrey Clemens are exemplars.

Meanwhile, skilled economic communicators like Don Boudreaux, Robert Murphy, and Steven Landsburg, have been patiently dissecting every last argument for the minimum wage. They’ve been originating countless new thought experiments, analogies, and parables to convey the consequences of price floors. And in many cases, they’ve pointed out the flaws in empirical studies, but I haven’t seen a one-stop-shop where these problems are succinctly described.

Here are five common reasons why minimum wage studies might fail to find an employment effect.

1. Non-Wage Margins of Adjustment

Price controls can’t stipulate every aspect of an exchange. Usually, the only contractual term they alter is price. Market participants are free to change other margins of the exchange, and the disequilibrium created by a (binding) minimum wage gives them an incentive to do so.

Gordon Tullock offered the following famous example. Imagine factory workers on a hot summer day. The plant manager gets the bright idea of cutting costs by shutting off the AC. Before long, the workers begin complaining. If the owner wishes to retain these workers, he’ll likely respond by flipping the AC back on—he doesn’t want to lose these laborers to the employer across town who offers better working conditions.

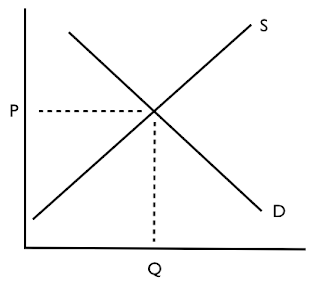

So how does the minimum wage alter this calculus? If it’s binding, it transforms a situation of market-clearing, the process of moving towards an equilibrium of quantity supplied and quantity demanded, into one of surplus. And a labor market surplus shifts power from sellers (laborers) to buyers (employers). A surplus of labor means a buyer’s market. Employers can pick and choose, and their offer on margins other than wage needn’t be as attractive as it had been.

Now when the plant shuts off the AC and the workers begin complaining, the owner metaphorically responds: “You don’t like it here? Feel free to leave. There are a hundred other workers who will take your place tomorrow.” The labor supply curve is at work to the employer’s advantage. More workers are entering this labor market due to the minimum wage (what economists refer to as the “extensive margin”). Notice something else: It will be harder for workers to find alternative employment precisely because a labor surplus prevails. As a result, the workers are less likely to leave and seek another job.

It’s, therefore, possible that a.) the total number of laborers employed remains unchanged and b.) employers restore profitability by cutting their electricity bill. Again, enabled by the “power” the minimum wage affords these employers.

Since economics is about tracing out the consequences of actions as far as possible, let’s go one step further. Suppose this employer has turned off the AC and suppose that many other employers have followed his cost-cutting lead. Taken together, they reduce the demand for electricity. In turn, this dampens the demand for all the workers who produce electricity. If this change is large enough, it’s easy to imagine that some of them lose their jobs as electricity producers adjust their production processes. There it is—unemployment caused by the minimum wage, but in a way so indirect that empirical analysis will be helpless to detect it.

Where would an empirical researcher begin looking to find this sort of unemployment? After all, my example used electricity, but this need not be where the relevant adjustment occurs (perhaps the employers stopped providing coffee in the lounge, for instance).

There are a few other ways these sorts of non-wage adjustments commonly manifest in labor markets, however. The employer can demand more and/or better work to justify the higher wages he is paying. The logic for why he can get away with this is identical to the AC example above. Practically, this may take the form of the employer trying to cut down on shirking, which is a “perk” of virtually all jobs (you’re not literally “laboring” for eight straight, uninterrupted hours on a workday). Putting it that way helps bring the parallel with the AC example into focus. The employer can take away your AC or he can take away your ability to shirk or some combination thereof.

One reason it’s so important to emphasize these adjustments is that they’re hard to detect with any empirical technique. For starters, it’s impossible to know where to look. Some firms will adjust on one margin, others on another. For another, it’s impossible to predict the time frame over which these marginal adjustments occur.

In what sense can we call these adjustments “job loss” if they leave the total number of workers unchanged? Well, part of a worker’s compensation has been “lost,” so this constitutes job loss in that sense. Same work, less pay. Or, more work, same pay. See Jeremy Clemens for an extensive examination of these adjustments in the face of the minimum wage.

Check back soon for other factors that can shipwreck minimum wage studies.